Compound Work

Field Notes on Practicing Resilience Under Pressure

In a moment when in-person time is precious and the stakes are high, our designs have to do more than feel good in the room.

This piece reflects on three recent retreat engagements—staff, managers, and a board—where the work had to build trust, develop skills, and produce real progress at the same time. It’s an argument for compound design: experiences that help organizations learn, adapt, and collaborate under pressure, not just talk about it.

I grew up in gyms; though looking back, they were little more than weight rooms. Bars, dumbbells, and benches.

The first one I really remember was at the end of a narrow corridor in my high school—no ventilation to speak of, a janky floor fan that shook violently but barely moved the air, and a battered radio in the corner with a cassette deck that the seniors unofficially had rights to commandeer on command. (When my turn came, I was no exception to the tradition.) It smelled awful—like stale sweat and clothes that had been living in lockers. The wrestlers, in particular, made it unbearable. Girls rarely passed the threshold of dude funk.

And yet, it mattered.

Working out became part of my life. In college, there were campus gyms. After law school, my first fitness club—the old Bally’s that swindled so many of us with their uncancellable membership. Over the years, I’ve always had access to a gym in one form or another. I literally made decisions where to live based on gym proximity. There had to be one within walking distance. So when I moved to D.C. during the pandemic, I finally built my own—turning my garage into something close to a fitness sanctuary. Anyone who knows me knows this about me. When people come to my house, I show them the gym.

What’s changed over time is how I use the gym.

I came up in a pretty straightforward lifting culture: lots of sets, lots of reps, plenty of time for talking and stalking—that thing Gymbro Sapiens do when they start feeling themselves. Two hours in the gym wasn’t unusual. These days, I don’t have that kind of time—or interest. What I’ve gotten deeply excited about instead is strength training in 30–45 minute windows, high intensity, highly intentional.

The key to making that work is compound exercises. Movements that do more than one thing at once. One lift, multiple muscle groups. Maximum return on limited time.

That idea—compound work—has quietly reshaped how I think about my professional practice.

In this season of my work, I’m being invited into in-person experiences that have become both rarer and more consequential. Retreats. Manager convenings. Board sessions. Moments when people are finally in the same room after months of distance, pressure, and churn.

The expectations placed on these gatherings are enormous. People want learning, connection, progress, and something tangible to show for the time. They want relief from fragmentation without pretending the world isn’t on fire.

And they want all of it at once.

A few years ago, I might have treated those needs as competing. Today, I don’t think they are. But meeting them requires designing differently. It has required me to become someone who intentionally loads compressed experiences so they do multiple kinds of work at the same time: skill-building, trust-building, strategy-making, and real production. I have come to think of this as compound design work, and what follows are three examples of what this looks like in practice.

Example One: When Equity Is a Systems Problem

Like many in this moment, a legal advocacy organization I’ve been working with for nearly two years found itself challenged on two fronts: grappling with whether its long-standing legal approach to impact litigation was still effective in the Trump era, and wrestling with how to continue advancing its values and commitments while operating under sustained strain. That tension was very much in the room when they asked me to design a day of deep staff dialogue and tangible action. I came to that work with an awareness that unless the anxiety around their legal and strategic questions was disentangled from the internal work of how people were operating together, the day would stall—frustrating some, flattening others. My charge, as I understood it, was to hold a space that allowed the organization to advance its equity work without pretending those larger questions weren’t present.

What I was hearing consistently was that ideas weren’t moving. People were bringing insight, concerns, and proposals into the system, and then—somewhere along the way—they disappeared. Not rejected exactly. Just absorbed. Delayed. Unclear.

Some of that was about siloing. Some of it was about remote work. Some of it was about hierarchy doing what hierarchy tends to do under pressure. And some of it—more quietly—was about equity.

Junior staff, in particular, had a deep, lived understanding of where the organization’s systems produced inequitable outcomes. And they didn’t assume it was because of bad intent. It was because of how decisions traveled, how feedback loops worked (or didn’t), and how accountability showed up differently depending on where you sat.

Before we could design anything, I had to slow the room down and get very clear about what we were even talking about.

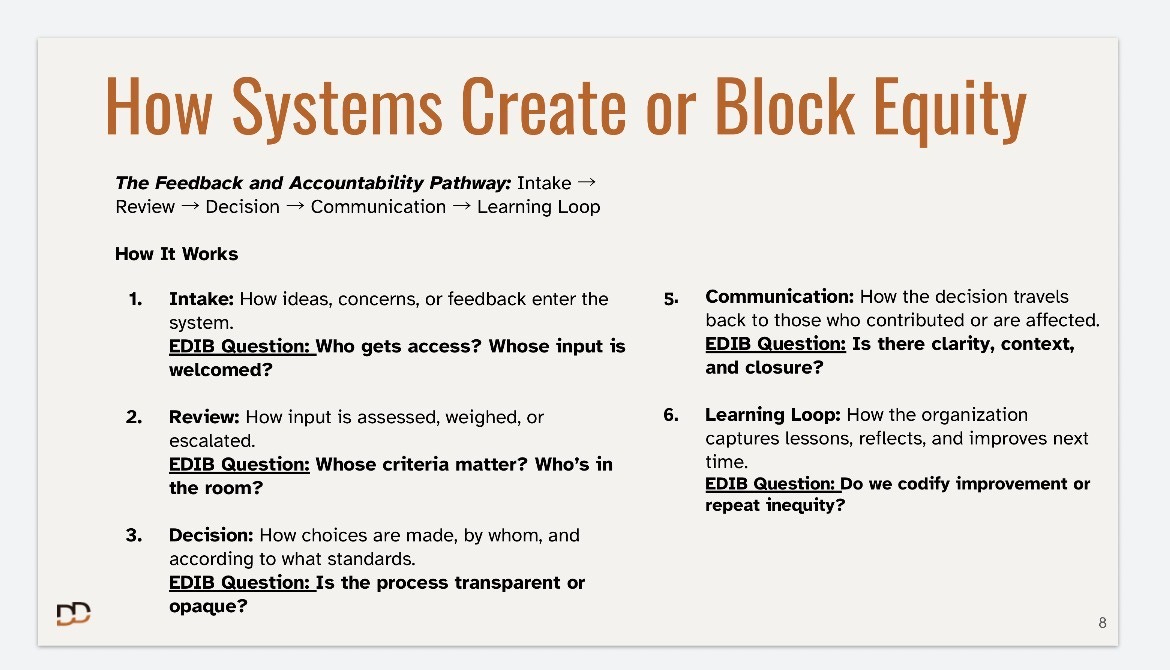

First, I explained that a system is a set of pathways, routines, and decisions that reliably produce outcomes. If those outcomes are inequitable, it’s often because the system is functioning exactly as designed.

Next, I made the system visible.

I walked them through a full cycle—intake, review, decision, communication, and learning—and showed how, at any point along that pathway, a breakdown could occur. Where loops fail to close. Where clarity dissolves. Where inequity gets produced not through intent, but through design.

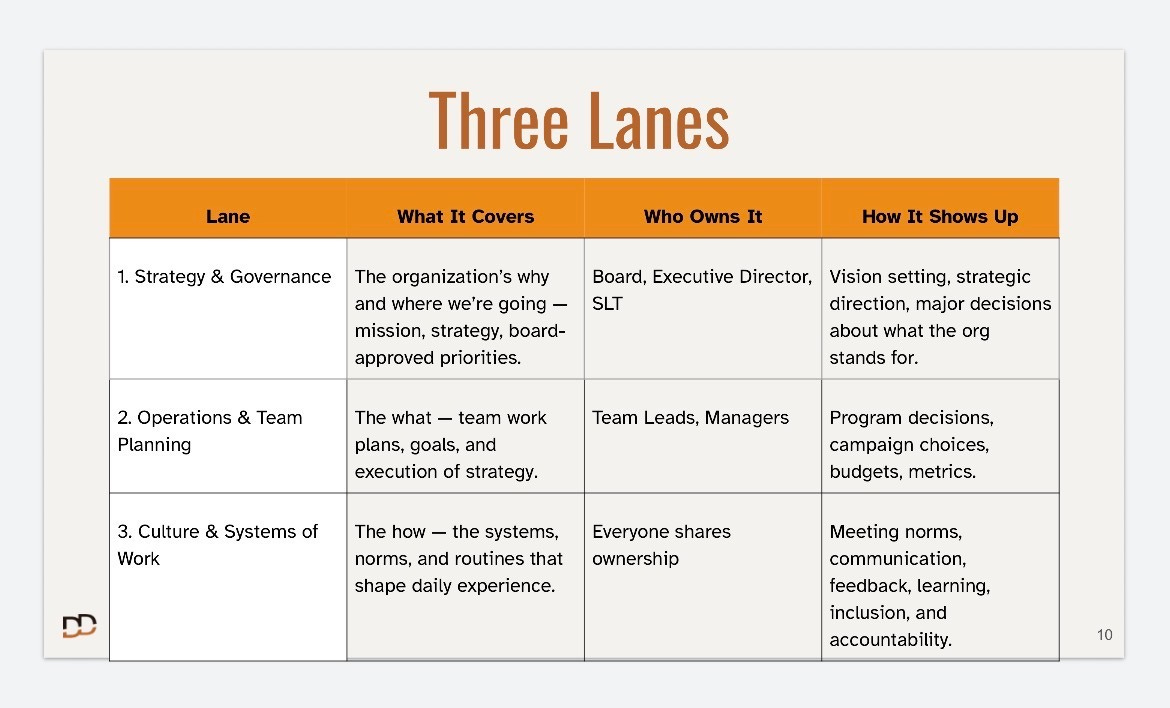

Then I introduced the idea that systemic equity operates across multiple layers at once, and named them explicitly:

governance and strategy

operations

culture and systems of work

In my experience, the distinction helps people stop locating equity solely in interpersonal behavior and begin to see how structure, process, and norms carry power. In the room, it allowed us to be clear about where the work for the day would live. While inequity can surface across governance, operations, and culture, our collective authority sat at the level of everyday systems and practices—and that’s where we focused our design work.

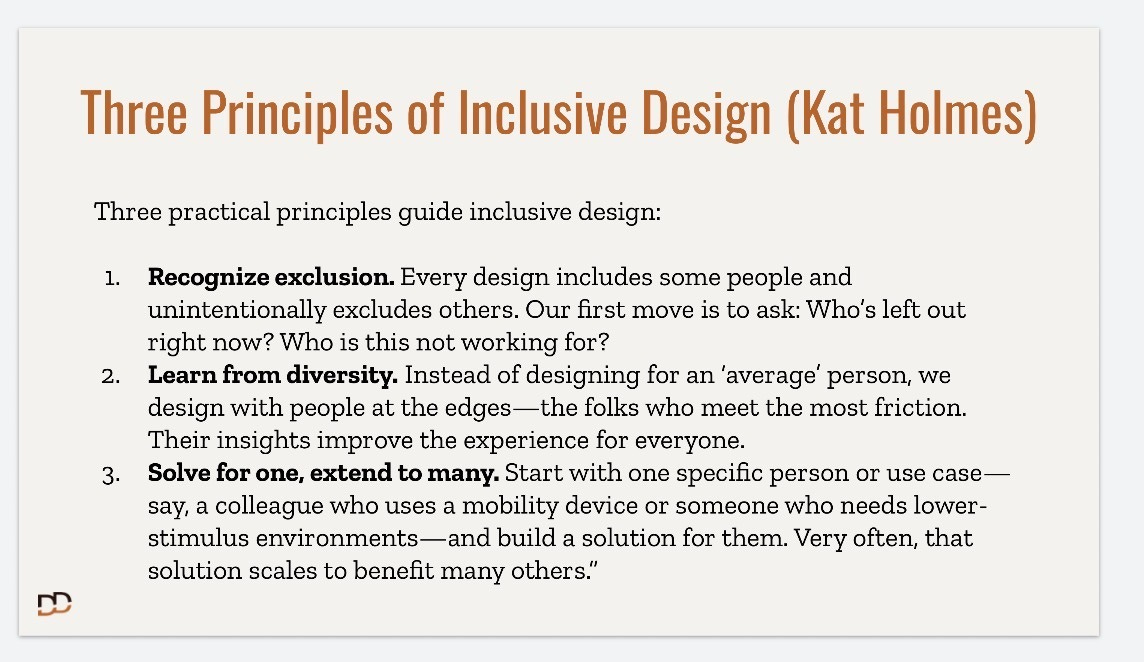

Only after that did we return to design for inclusion—a set of principles I had introduced in a previous session and wanted to bring back into active use. The idea was simple but demanding: when you design for the person most likely to be excluded, you don’t diminish the experience for others—you strengthen the system.

The design challenge I gave them was concrete. Using the organization’s real challenges around feedback and accountability—issues that were showing up as equity problems—they were asked to design a small, testable intervention that would interrupt those patterns.

The process required them to slow down:

What is the current state?

Where does the breakdown occur?

Who is most impacted?

What would it mean to design differently here?

And then came the compound move.

In a previous session, the group had identified facilitation as a capability they wanted to strengthen. So instead of report-backs, I asked for teach-backs. Each group had to use one or two facilitation moves I had shared with them to bring the rest of the room into their thinking—practicing not just what they designed, but how ideas travel.

By the end of the session, several things had happened at once:

people shared a language for equity as a systems challenge

they practiced slowing themselves down enough to design

facilitation became a shared muscle

and they produced real prototypes that could be piloted within sixty days

The work didn’t end in the room. It moved. That’s compound work.

Example Two: Sensemaking Under Pressure

The second example comes from a large national organization that is quite literally in the crosshairs of the partisan divide. They have faced real reprisal from the Trump administration. Not threats. Not theory. Real consequences.

They know with 100% certainty that the year ahead will bring major disruption.

I had worked with this organization previously, introducing resilience as a framework and helping them assess whether they were actually building adaptive capacity or simply enduring. We talked about resilience as the ability to learn, coordinate, and adapt under repeated stress. The archaeological research on societies exposed to frequent disruption resonated deeply with them. They recognized themselves in it.

This convening brought together more than sixty people managers—many of them in the same room for the first time. Tensions existed. Union dynamics were live. The political environment was ever-present. This was not a group that could tolerate learning disconnected from reality.

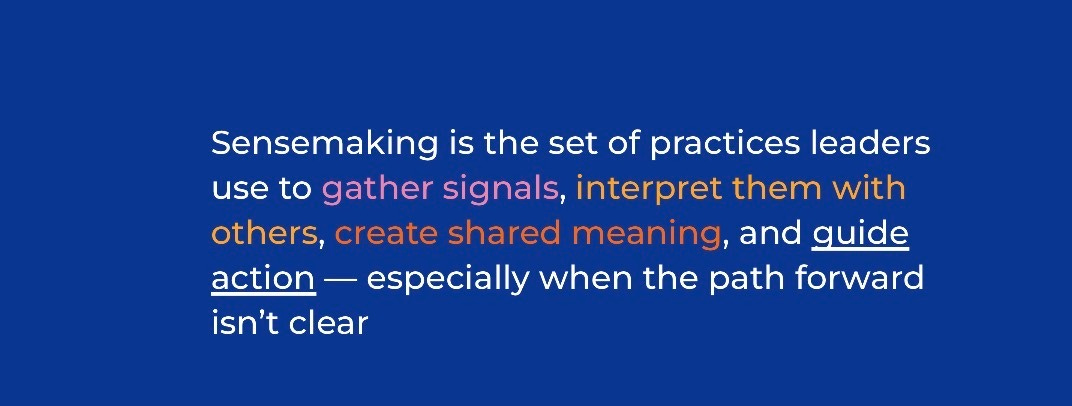

I began by introducing sensemaking as a leadership behavior and practical skill that is known but underdeveloped and unevenly practiced. I named it so they could share language for what they were already doing—and what they needed to do together.

Sensemaking, as I framed it, is inherently collective. It is how groups interpret incomplete information without fracturing or defaulting to urgency.

Then we practiced.

The core of the session was a departmental simulation built around a triggering external event. Information arrived in waves. Impacts rippled across departments. Teams had to respond with partial information, aware that their choices affected the whole system.

As the simulation unfolded, something powerful happened.

Senior leaders—some of the most senior executives in the organization—stood and spoke openly about how they had operated in similar moments. Why they made the choices they did. Where urgency had shaped behavior. The CEO herself spoke passionately about wanting a different way of moving forward.

Once that happened, the room changed.

The conversation turned toward the future. Toward what a shared playbook might require. And the ideas came. They were specific, thoughtful, grounded. They were not aspirational slogans, but real practices for coordination under disruption.

By the end of the session:

sensemaking had been anchored as a shared leadership practice

disruption was treated as a design condition, not an interruption

senior leadership modeled accountability in real time

and the group began constructing the components of a playbook for the year ahead

Resilience wasn’t declared. It was rehearsed. That’s compound work.

Example Three: Governance as a Design Problem

The third example takes place in a boardroom.

This was a large social service agency with a traditional, highly credentialed board. Senior leaders from multiple industries. Steeped in the rituals of governance: strategy, budgets, CEO evaluation.

The organization asked me to come in because something wasn’t quite working anymore.

They wanted the board to feel more connected to one another as people beyond their affiliation with the organization. They were transitioning from a long-standing, influential board chair to a co-leadership model still establishing its authority. Interviews revealed a consistent pattern: broad support for anti-racism in principle, but uncertainty about how it connected to governance and strategy.

Engagement in meetings was imbalanced. Dominant voices shaped conversation. Newer members, still acclimating to a culture shaped by long-tenured board members, didn’t know how to enter and be useful. And their own uncertainty was influencing their fundraising goals.

The design challenge was about giving board members the space and conditions to build the habits, confidence, and shared reference points that would allow more people to enter the conversation and contribute meaningfully.

I designed the retreat around a series of board-level design sprints. In small, intentionally mixed groups, board members worked on real governance challenges—translating anti-racism into strategy, redefining risk, and strengthening engagement.

The structure did important work without calling attention to itself. As the sprints unfolded, dominance softened, participation widened, and values began to move from abstraction into practice. Board members produced tangible artifacts—prototypes they could test and refine—but just as importantly, something shifted in how the board experienced itself.

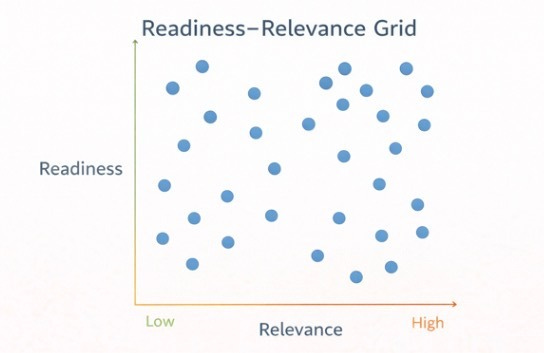

To capstone the work, we closed with what I call a relevance–readiness pulse check. I asked board members to look across the different prototypes they had just encountered and, rather than defaulting to what they liked or didn’t like—a move that can be difficult in groups where trust is still forming—to assess each one along two dimensions: relevance and readiness.

Plotting the prototypes this way allowed the group to see them not as competing ideas, but as distinct possibilities at different stages of organizational maturity. It gave the board a shared, non-defensive way to talk about what could move now and what might need more time.

By the end:

trust was built through shared work

voice redistributed without confrontation

new leadership gained insight into board dynamics

the board experienced itself as a learning system

and the group developed a shared sense of where momentum actually existed across the prototypes

That’s compound work.

Designing for the Moment We’re In

I’m sharing these examples because they’re becoming necessary. In a moment when in-person time is precious and pressure is constant, the margin for work that feels good but doesn’t travel beyond the room has disappeared. At the same time, the needs for community, learning, strategy, progress, and resilience practice remain fully present. Meeting this moment asks more of how we design: not just good experiences, but structures, practices, and artifacts that hold up once people return to the work.

Compound design asks more of the people in my position. It requires deeper listening and more braided planning, along with a willingness to draw deliberately from multiple disciplines—systems thinking, inclusive design, group psychology, facilitation, organizational development, resilience research, and even fitness and training logic—rather than relying on any single toolkit. Most of all, it asks us to be honest about the disruption our partners and the organizations we serve are living through, while still supporting their ongoing effort to build internal capabilities that reflect their values—and to design in ways that can hold those realities and help move the work forward.

If the pressure is real, the design has to be real too.

That’s compound work.