Because Today is Not Yesterday

Reflecting on Five Years of Equity and Inclusion Wins and Preparing for Road Ahead

[Two weeks after the election, I gave a talk on my past five years in the racial equity space to the staff of the Nonprofit Finance Fund. I wanted to capture the wins that I have witnessed/been part of over the past half-decade, reckon with where we have fallen short, and offer some sober-minded perspective for navigating the future that awaits us come January. This essay is the second of a three-part end-of-year series I’m writing on the past, present and future of equity work.]

Two summers ago I was at the airport, on my way to a summer vacation with my family when I happened to check my email. I had just gotten through TSA and was walking to my gate at Reagan National, mindlessly killing time as I knew we had some time before our flight. That’s when I saw a message. It was from President Joe Biden.

Now, by way of context, I should point out that one month earlier, the Supreme Court had struck down the administration’s plan to cancel $400 billion in student debt, effectively killing the administration’s most ambitious and controversial efforts to address racial inequity, the wealth gap and the economic disparities burdening younger Americans in a single swoop.

I actually wasn’t part of that cohort and wouldn’t have benefited from the relief it offered. I was no longer in the public service sector and my income exceeded the limits. And while I was a little bummed, I wasn’t bitter and pissed off just because I wasn’t going to personally benefit from the new policy. On one hand, as a Gen Xer, I’ve come to accept that, by and large, we are considered an afterthought —the invisible middle children caught between larger, louder generations who just go about our business. If anything, I saw this as an opportunity to embrace the equity values that I spend most of my working hours thinking about and challenging so many others to live into.

Before the Supreme Court blocked it, I’d had debates with friends about Biden’s relief plan—which, by the way, was fairly modest in that it was capped at $20,000. All of these friends would identify as left of center if asked yet they disliked the notion of the government forgiving students and former students of crushing debt. “They took on the debt,” they’d say. “It would cost the rest of us too much.” My reply was that leveling the playing field sometimes requires choices that benefit those who have been left behind. Moreover, the debt was a drag on the economy and exacerbated the racial wealth gap. Somehow, my words never seemed to change their minds. I discovered then that even amongst allies, there can be a fixedness, an unwillingness to seriously entertain initiatives that put our hang-wringing about inequality into action.

Once the Supreme Court decision came down, I figured, as with the Affirmative Action decision that preceded the student debt ruling by one day, the story was over. The administration had attempted to make good on its promise but by 2023 the racial justice backlash that began essentially with the storming of the Capitol in January 2021 had taken hold, reasserting white supremacy as the unwritten law of the land.

But then I read the subject line. It was regarding my student loans. I clicked on the message, assuming it was some generic announcement about the administration’s failed effort. So you can imagine my shock when I read, “Your Federal Student Loan Has Been Forgiven”. I stopped in my tracks, allowing the crowds of people hustling to make their flights to brush past me while reading the email again, and then again.

It turned out that the administration had advanced multiple efforts to address the student debt crisis and while the one that garnered headlines had been quashed, others continued on without the need for court approval. In my case, I had been paying consistently against an income driven repayment agreement–one that had been shuttled from one processor to the next so many times that I had lost track–that was supposed to provide me with relief after 20 years but hadn’t, largely because the federal government had failed to oversee and enforce my rights and the processors were all too happy to keep taking my money. As such, the cancellation was based on an affirmative, binding and enforceable contractual relationship between the Department of Ed. and processing companies that did not raise any constitutional concerns.

So what did this mean in real terms–with that single email, a $90,000 debt disappeared. More than that, this cloud that had hovered over my entire adult life, that had in many ways been a drag on my ability to build wealth–wealth my parents who grew up under jim crow–had not been able to accumulate at the same clip as their peers and could therefore not pass down to me or share with me to offset my college costs, was gone. This debt had been my secret shame, an albatross that no matter how much I paid on it never seemed to shrink. I felt I had done something wrong or that my inability to erase the debt was a sign of failing at life. The debt undermined my confidence in myself. For a long time, its existence caused me to delay settling down, having children, and buying a home. Even now, when I look at some of my longtime friends, I am a full decade behind in terms of the life markers that we typically associate with adulthood. I got married later, had children later and bought a home later.

Is that all because of student debt? No, of course not. But it was a contributing factor.

I can’t begin to tell you what the walk to the gate felt like. I felt, suddenly but definitely not inexplicably, freer. In an instant, I could see my future in a different light. This is the power of racial equity work, what it can mean to a single individual–in this case, me. I am among the nearly 5 million Americans who have seen their student debt canceled, amounting to over $175 billion refunded to us so that we can move forward with our lives and invest in this country’s future.

I started with this story because I think that right now in particular we need to be in deep reflection on what the last four years have meant for us. We are down. We are sad. We have every right to feel uncertain about what the future holds. But for those of us who are fuzzy about what is different now than it was before, let’s be very clear with each other–things have changed. We are not in the same place we were in November 2020. Have we realized the dreams we allowed ourselves to aspire for when the country seemed, finally, to be awakening and owning its racist history? Perhaps not. Since the insurrection, it has felt like a slog. Book bans, Stop woke bills, Dobbs, unfulfilled DEI commitments, Diversity under fire left and right. And now the reality of a second Trump presidency. I do not blame you for feeling defeated, and yet I want to offer another prism through which to experience this moment. Two in fact.

First, we have done a lot in the past four years. Forget the naysayers who nag us about whether DEI has made an impact; who say it hasn’t led to any change; the fact is it would not have come under fire otherwise. If we were so ineffective then we would not be facing such a fierce backlash.

Let’s start with the administration. For a moment, let's put aside our criticism of its shortcomings, of which there are many, and look at its racial equity record. If you recall, Biden’s day one executive orders included a sweeping Racial Equity mandate. Since then, and in addition to the student debt relief, the administration has secured $2 billion in reparations for Black farmers who were excluded from federally backed loans that their white counterparts were able to access, and combatted redlining through a Department of Justice initiative that has secured $150 million from banks for redlined communities. The DOJ has gone after racist home appraisers who have devalued Black homes. The Consumer Protection Bureau, which Elon Musk is threatening to obliterate has promulgated rules to prevent predatory commercial practices, junk fees among them, that disproportionately target and steal wealth from underresourced Black and Brown communities. It has helped amplify the movement to cancel medical debt, which disproportionately impacts people of color, by proposing a ban on credit reports including medical debt.

Looking beyond the White House, a number of local and state governments have passed laws to require employers to post salary ranges. Paid parental leave for both parents is now the expectation not the exception. We have seen a resurgence in labor and the power of collective bargaining is being exerted in industries (retail, logistics, arts and culture, advocacy, and more) that up to a few years ago fancied themselves above the need for workers rights.

This was not the case in 2019, y’all. It just wasn’t

Within nonprofit organizations–and I have been inside a lot of them for the past five years–hiring practices have become more formalized and rigorous. The departments previously known as “HR” now refer to themselves as “People and Culture,” priding themselves less on administrative order than on consciously interrupting implicit bias and designing processes and practices (diverse hiring panels for instance) to mitigate the power of group think. Organizations have undertaken pay equity audits and made adjustments based on the market and on disparities within. I am witnessing the building of formal and transparent compensation and promotions practices. We have seen the emergence of a consciousness around wellness, burnout and psychological safety. Office spaces have been redesigned to accommodate the hybrid work zeitgeist. Even as some CEOs push for a full-stop RTO, many continue to experiment with flexible work schedules and hybridity because the bottom line benefits are undeniable. Some orgs have tried to flatten hierarchies and distribute leadership models. It may not be the norm or the best fit for all, but it is not unusual to see co-executive directors. More recently, I have seen organizations broaden their senior leadership teams to include and empower vice presidents and directors as a way to build more inclusive, accountable leadership cultures.

This list of shifts over the past four years is not exhaustive and it is not meant to suggest that everything is ok. Because it’s not and I don’t want my words to be misconstrued. It is merely meant to remind us in this moment when we are spinning and feeling we have not done anything, that we have made progress! We are not where we were four to five years ago. Before the pandemic, it would have been an anomaly for our strategic plans to embed equity as both a feature of process decision and projected outcome. Most orgs could not articulate how their work addressed systems of oppression or advanced equity and justice. They were not aware of the effects of redlining or the racism within our health care system. We were not talking about power or race. Most of us did not know what intersectionality meant. The too often counterproductive manner in which it has been wielded within orgs notwithstanding, white supremacy has been metabolized and broadly acknowledged as a barrier we must name and navigate if we truly want to re-make our orgs into space where our multiple ways of knowing, being and doing can thrive. We had no discourse around the generational divide or how to navigate it. Most of us had never heard of decolonization. Concepts like weathering and its impact on people of color were unknown to most of us.

A dear friend was recently diagnosed with breast cancer. After doctors dismissed her concerns about a cyst, a pair of physician friends urged her to get an immediate biopsy, warning of the health care system's bias against Black bodies. Their advice—grounded in their awareness from racial equity trainings that we so often malign—may have saved her life. Those doctor friends were white.

The upshot is that we all have new lenses, language and understanding that we did not previously have.

The most visible shift in our sector has been the ascendence of leaders of color, particularly women. Starting after George Floyd and the racial reckoning, my LinkedIn feed exploded with jubilant job announcements, many of them long overdue. Finally, after years of being told we couldn’t fundraise or that we didn’t have the right experience without being provided clarity regarding what that even meant or how we could get it, leaders of color started being seen and promoted into positions of senior leadership.

This is also where things got tricky. In many ways, we were not ready for these leaders. We wanted them to look different, to better represent impacted communities and reflect the diversity of our sector. We were not always ready for these leaders to be their authentic selves, individuals rather than archetypes. I’ve had the chance to peek inside dozens of organizations undergoing leadership transitions and a resounding, perpetual theme has been that after a period of elation, the new leader of color faces a level and type of pressure and scrutiny that their predecessors did not. And that extra scrutiny led many of them to leave or be pushed out.

This isn’t a defense of incompetence or bad leadership. It isn’t to presume that every piece of luggage the new leaders bring in the door should be given quarter. It is, however, important for us to reflect, in this moment especially, on the expectations that we have of our leaders of color. I wrote about this last year for NPQ and call it the Black Leader’s Burden. By which I mean: the additional weight leaders of color are saddled with beyond the job is both a function of the gauntlet we require them to run to get into the c-suite and the unrealistic expectations that we place on them to fix our brokenness.

What were we holding in our heads and hearts when the new leader of color was hired? Did we expect them to be our friend? Our mentor? Our healer? Our savior? What I have found is that the unspoken expectation has been for the new leader of color to take care of the organization and the people in ways their white counterparts and predecessors were not. And as we ask ourselves why America chose a mean, entitled, bigoted, dangerous, morally abhorrent man with a criminal record over a woman of color who dedicated her life to service, we have to ask not only how we could let this happen but how the traces of white supremacy and patriarchy live within our organizations as well.

This past year I had the unique opportunity to partner with an organization to write its racial equity and inclusion story. I’d worked with the organization for several years, which was long enough to convince me that racial equity wasn’t a service they provided but a way of being in the world. I wanted to understand how they had gotten there. Initially, they hesitated. They invariably reminded me that they were still a work in progress and had a long way to go. To which I steadfastly replied, who isn’t. Moreover, that is the point. Those of us who are doing work that can broadly be classified under the DEI banner have not done ourselves any favors by not openly, persistently and aggressively telling our stories. Because we have this notion that we are going to arrive at this future destination at which point we will be ready to talk about how we made it coupled with deep fear around how we will be perceived, everyone who has sat through an unconscious bias training and felt the slightest bit annoyed that it didn’t solve all of the organization’s problems overnight has had free reign to thoroughly shape the public’s understanding of the work.

Eventually, I convinced them to trust me. The first request that I made to the team once we agreed to the project was to see everything the firm had done to date. Within a few days, we received a link to a suite of folders containing rubrics, survey results, and memos all going back several years. We were amazed by what we encountered. The firm had been capturing its journey and tracking its progress all along. More directly: what I discovered in those folders was that the organization wasn’t just telling others what to do and how to do; it had turned the lens inward to do its own rigorous racial equity work. The more we learned about the firm’s internal, relational work through our interviews, the more convinced we became that this was what readers could relate to and could learn from.

All told, we spoke with two dozen current and former staff, board members, affiliates and foundation partners. These folks were generous and courageous in their sharing. They told hard stories of hurt feelings and unmet expectations, but they also told us about the organization’s persistence and its progress. Our task was to blend their voices along with the documents that we reviewed into a series of digestible narratives that deliver insight and action steps. Broken into eight distinct but overlapping chapters, the result is a series of vignettes that revolve around one organization’s efforts to advance, amend, embrace and embed our shared racialized inheritance across a period of time that began roughly a decade ago.

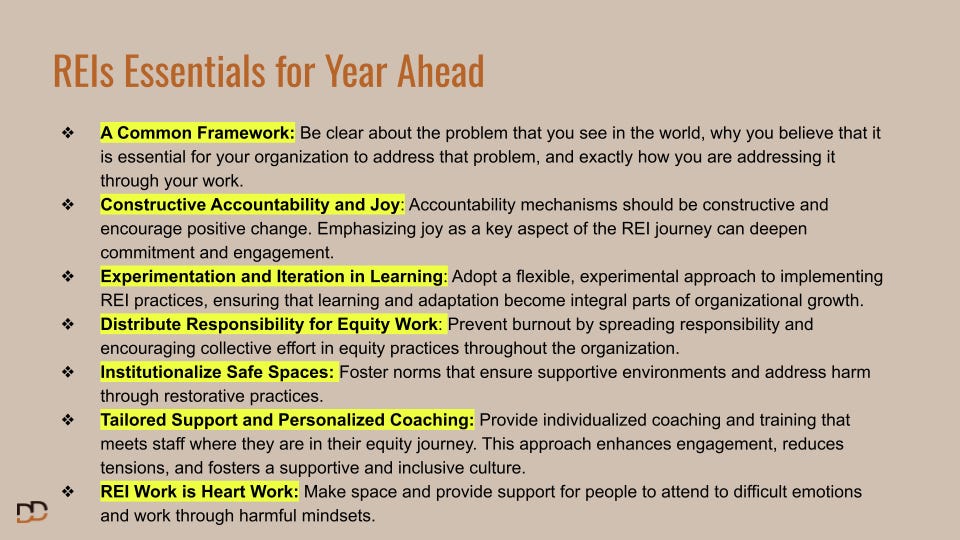

So what did we discover? A lot. But while the whole list is rich and will be sure in 2025, I’ve chosen a handful that I believe are essential to practice in the coming year. As you read them, I only ask that you think about these questions for yourself, on your own. That’s all:

Where do you see your own opportunities to lead or grow?

Where do you need more guidance and clarity from leadership?

What do you deeply desire for your organization?

What is the most essential work that you believe your organization needs to do at this moment to continue advancing its DEI?

I want to end this with a pair of reflections and an offering that has helped me remain hopeful.

The first: I recently led a series of REI workshops for an organization that works on one of our most urgent issues. It was a good work and people gave what they could. But what I found, by and large, was that people were too burned out to engage in the work being asked of them. It disappointed me because, as I pointed out to them and believe it to be true, they can’t do their best work if they can’t talk openly and honestly with one another. They can’t change the systems if they can’t be real with one another. Their best ideas won’t flourish. Fresh voices from unsuspecting corners of the organization won’t be heard–heck they won’t speak up. Yet even after I said this, folks remained silent, off camera–eyes averting each other. I got it. I understood.

The second: A few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a long profile on the University of Michigan’s decade long DEI efforts. This section really stood out to me:

“D.E.I. 1.0, the school promised, would be rigorous and evidence-based. Each of the university’s dozens of “units,” from the medical school down to the university archives, was instructed to devise its own plan; many set up miniature D.E.I. offices of their own. The initial planning ultimately yielded nearly 2,000 “action items” across campus — a tribute to Michigan’s belief in the power of bureaucratic process to promote change. “It’s important to focus on our standard operating procedures and worry less about attitudes,” said Sellers, who was appointed Michigan’s first chief diversity officer. “Attitudes will follow.”

The article’s conclusion was that the university has spent millions yet the progress it has made to date has been, at best, modest and more likely non-existent. More recently, and in part due to the article, the university has started rolling back its DEI practices.

In planning to spend time with you, I thought about both of these encounters. To me, there is a link between them. My hypothesis is that, for now, and especially as it relates to our external work, we have reached an impasse. It may be the case that because of the social and political climate we are entering we won’t be able to influence the external environment for the foreseeable future.

Our inability to directly influence and shape the external environment in alignment with our values could cause us to turn further inward, to close ourselves off from one another. It could fuel further angst and distrust and erode our coalitions from within.

Or it could be the invitation that we need to reconnect with one another. In hindsight, the period that will always be known as the racial reckoning was imperfect in many ways, but the trauma that we shared bonded us and through those bonds we had conversations. I’m not suggesting that we need to return to that time, but we are entering a dark period and we will have decisions to make about how we are going to extend ourselves, especially in these remote environments, to bridge our communities.

The silver lining here is that the renaissance of equity work that I believe we have been living through over the past handful of years was, in fact, the outgrowth of decades of darkness. My belief is that we were ready with action items because many of us had spent extended time in the shadows refining our ideas within our quiet communities, waiting for the right opportunity to bring them forward into the world. We didn’t just find out about discriminatory hiring practices in 2020. That research was two decades old when it finally started to result in reforms. The same can be said of Brown v Board. We know that 1954 was the year of that landmark decision but Thurgood Marshall spent the better part of 20 years building the case law and precedent so that when the moment finally arrived, the NAACP was ready. And let’s keep in mind, America didn’t pass its first federal anti-lynching legislation until 2022.

All of which is to say, we have work to do. Even if that work won’t result in changes tomorrow or the next day, that work is important because it lays groundwork for the next wave of opportunity, which, history and the laws of physics dictate, will come. So we can be down on each other or we can use this time to strategically plan the next phase of the struggle. We can, as Sherrilyn Ifilll wrote on her Substack the day after the election, plant the many seeds that we will need to grow in the years and decades ahead. If we do, though, we are going to have to recommit ourselves to being in a relationship with one another.

So today I want to end with the work of the poet, Audre Lorde. In 1982, Lorde delivered a talk at Harvard on the occasion of a celebration of Malcolm X's life and legacy in which she reflected on the 1960s. The essay is 42 years old but she speaks to the collateral damage of the reckoning we find ourselves in today

“In the 1960s, the awakened anger of the Black community was often expressed, not vertically against the corruption of power and true sources of control over our lives, but horizontally toward those closest to us who mirrored our own impotence. We were poised for attack, not always in the most effective places. When we disagreed with one another about the solution to a particular problem, we were often far more vicious to each other than to the originators of our common problem.”

That disagreement eroded the energy that folks needed to fight. It depleted folks. It burned them out. So, for Lorde back then and for me now, I offer the following reminder, coda, call to solidarity–whatever it needs to be to bring us into community.

“You do not have to be me in order for us to fight alongside each other. I do not have to be you to recognize that our wars are the same. What we must do is commit ourselves to some future that can include each other and to work toward that future with the particular strengths of our individual identities. And in order to do this, we must allow each other our differences at the same time as we recognize our sameness.”

Two summers ago I was at the airport, on my way to a summer vacation with my family when I happened to check my email. I had just gotten through TSA and was walking to my gate at Reagan National, mindlessly killing time as I knew we had some time before our flight. That’s when I saw a message. It was from President Joe Biden.

Now, by way of context, I should point out that one month earlier, the Supreme Court had struck down the administration’s plan to cancel $400 billion in student debt, effectively killing the administration’s most ambitious and controversial efforts to address racial inequity, the wealth gap and the economic disparities burdening younger Americans in a single swoop.

I actually wasn’t part of that cohort and wouldn’t have benefited from the relief it offered. I was no longer in the public service sector and my income exceeded the limits. And while I was a little bummed, I wasn’t bitter and pissed off just because I wasn’t going to personally benefit from the new policy. On one hand, as a Gen Xer, I’ve come to accept that, by and large, we are considered an afterthought —the invisible middle children caught between larger, louder generations who just go about our business. If anything, I saw this as an opportunity to embrace the equity values that I spend most of my working hours thinking about and challenging so many others to live into.

Before the Supreme Court blocked it, I’d had debates with friends about Biden’s relief plan—which, by the way, was fairly modest in that it was capped at $20,000. All of these friends would identify as left of center if asked yet they disliked the notion of the government forgiving students and former students of crushing debt. “They took on the debt,” they’d say. “It would cost the rest of us too much.” My reply was that leveling the playing field sometimes requires choices that benefit those who have been left behind. Moreover, the debt was a drag on the economy and exacerbated the racial wealth gap. Somehow, my words never seemed to change their minds. I discovered then that even amongst allies, there can be a fixedness, an unwillingness to seriously entertain initiatives that put our hang-wringing about inequality into action.

Once the Supreme Court decision came down, I figured, as with the Affirmative Action decision that preceded the student debt ruling by one day, the story was over. The administration had attempted to make good on its promise but by 2023 the racial justice backlash that began essentially with the storming of the Capitol in January 2021 had taken hold, reasserting white supremacy as the unwritten law of the land.

But then I read the subject line. It was regarding my student loans. I clicked on the message, assuming it was some generic announcement about the administration’s failed effort. So you can imagine my shock when I read, “Your Federal Student Loan Has Been Forgiven”. I stopped in my tracks, allowing the crowds of people hustling to make their flights to brush past me while reading the email again, and then again.

It turned out that the administration had advanced multiple efforts to address the student debt crisis and while the one that garnered headlines had been quashed, others continued on without the need for court approval. In my case, I had been paying consistently against an income driven repayment agreement–one that had been shuttled from one processor to the next so many times that I had lost track–that was supposed to provide me with relief after 20 years but hadn’t, largely because the federal government had failed to oversee and enforce my rights and the processors were all too happy to keep taking my money. As such, the cancellation was based on an affirmative, binding and enforceable contractual relationship between the Department of Ed. and processing companies that did not raise any constitutional concerns.

So what did this mean in real terms–with that single email, a $90,000 debt disappeared. More than that, this cloud that had hovered over my entire adult life, that had in many ways been a drag on my ability to build wealth–wealth my parents who grew up under jim crow–had not been able to accumulate at the same clip as their peers and could therefore not pass down to me or share with me to offset my college costs, was gone. This debt had been my secret shame, an albatross that no matter how much I paid on it never seemed to shrink. I felt I had done something wrong or that my inability to erase the debt was a sign of failing at life. The debt undermined my confidence in myself. For a long time, its existence caused me to delay settling down, having children, and buying a home. Even now, when I look at some of my longtime friends, I am a full decade behind in terms of the life markers that we typically associate with adulthood. I got married later, had children later and bought a home later.

Is that all because of student debt? No, of course not. But it was a contributing factor.

I can’t begin to tell you what the walk to the gate felt like. I felt, suddenly but definitely not inexplicably, freer. In an instant, I could see my future in a different light. This is the power of racial equity work, what it can mean to a single individual–in this case, me. I am among the nearly 5 million Americans who have seen their student debt canceled, amounting to over $175 billion refunded to us so that we can move forward with our lives and invest in this country’s future.

I started with this story because I think that right now in particular we need to be in deep reflection on what the last four years have meant for us. We are down. We are sad. We have every right to feel uncertain about what the future holds. But for those of us who are fuzzy about what is different now than it was before, let’s be very clear with each other–things have changed. We are not in the same place we were in November 2020. Have we realized the dreams we allowed ourselves to aspire for when the country seemed, finally, to be awakening and owning its racist history? Perhaps not. Since the insurrection, it has felt like a slog. Book bans, Stop woke bills, Dobbs, unfulfilled DEI commitments, Diversity under fire left and right. And now the reality of a second Trump presidency. I do not blame you for feeling defeated, and yet I want to offer another prism through which to experience this moment. Two in fact.

First, we have done a lot in the past four years. Forget the naysayers who nag us about whether DEI has made an impact; who say it hasn’t led to any change; the fact is it would not have come under fire otherwise. If we were so ineffective then we would not be facing such a fierce backlash.

Let’s start with the administration. For a moment, let's put aside our criticism of its shortcomings, of which there are many, and look at its racial equity record. If you recall, Biden’s day one executive orders included a sweeping Racial Equity mandate. Since then, and in addition to the student debt relief, the administration has secured $2 billion in reparations for Black farmers who were excluded from federally backed loans that their white counterparts were able to access, and combatted redlining through a Department of Justice initiative that has secured $150 million from banks for redlined communities. The DOJ has gone after racist home appraisers who have devalued Black homes. The Consumer Protection Bureau, which Elon Musk is threatening to obliterate has promulgated rules to prevent predatory commercial practices, junk fees among them, that disproportionately target and steal wealth from underresourced Black and Brown communities. It has helped amplify the movement to cancel medical debt, which disproportionately impacts people of color, by proposing a ban on credit reports including medical debt.

Looking beyond the White House, a number of local and state governments have passed laws to require employers to post salary ranges. Paid parental leave for both parents is now the expectation not the exception. We have seen a resurgence in labor and the power of collective bargaining is being exerted in industries (retail, logistics, arts and culture, advocacy, and more) that up to a few years ago fancied themselves above the need for workers rights.

This was not the case in 2019, y’all. It just wasn’t

Within nonprofit organizations–and I have been inside a lot of them for the past five years–hiring practices have become more formalized and rigorous. The departments previously known as “HR” now refer to themselves as “People and Culture,” priding themselves less on administrative order than on consciously interrupting implicit bias and designing processes and practices (diverse hiring panels for instance) to mitigate the power of group think. Organizations have undertaken pay equity audits and made adjustments based on the market and on disparities within. I am witnessing the building of formal and transparent compensation and promotions practices. We have seen the emergence of a consciousness around wellness, burnout and psychological safety. Office spaces have been redesigned to accommodate the hybrid work zeitgeist. Even as some CEOs push for a full-stop RTO, many continue to experiment with flexible work schedules and hybridity because the bottom line benefits are undeniable. Some orgs have tried to flatten hierarchies and distribute leadership models. It may not be the norm or the best fit for all, but it is not unusual to see co-executive directors. More recently, I have seen organizations broaden their senior leadership teams to include and empower vice presidents and directors as a way to build more inclusive, accountable leadership cultures.

This list of shifts over the past four years is not exhaustive and it is not meant to suggest that everything is ok. Because it’s not and I don’t want my words to be misconstrued. It is merely meant to remind us in this moment when we are spinning and feeling we have not done anything, that we have made progress! We are not where we were four to five years ago. Before the pandemic, it would have been an anomaly for our strategic plans to embed equity as both a feature of process decision and projected outcome. Most orgs could not articulate how their work addressed systems of oppression or advanced equity and justice. They were not aware of the effects of redlining or the racism within our health care system. We were not talking about power or race. Most of us did not know what intersectionality meant. The too often counterproductive manner in which it has been wielded within orgs notwithstanding, white supremacy has been metabolized and broadly acknowledged as a barrier we must name and navigate if we truly want to re-make our orgs into space where our multiple ways of knowing, being and doing can thrive. We had no discourse around the generational divide or how to navigate it. Most of us had never heard of decolonization. Concepts like weathering and its impact on people of color were unknown to most of us.

A dear friend was recently diagnosed with breast cancer. After doctors dismissed her concerns about a cyst, a pair of physician friends urged her to get an immediate biopsy, warning of the health care system's bias against Black bodies. Their advice—grounded in their awareness from racial equity trainings that we so often malign—may have saved her life. Those doctor friends were white.

The upshot is that we all have new lenses, language and understanding that we did not previously have.

The most visible shift in our sector has been the ascendence of leaders of color, particularly women. Starting after George Floyd and the racial reckoning, my LinkedIn feed exploded with jubilant job announcements, many of them long overdue. Finally, after years of being told we couldn’t fundraise or that we didn’t have the right experience without being provided clarity regarding what that even meant or how we could get it, leaders of color started being seen and promoted into positions of senior leadership.

This is also where things got tricky. In many ways, we were not ready for these leaders. We wanted them to look different, to better represent impacted communities and reflect the diversity of our sector. We were not always ready for these leaders to be their authentic selves, individuals rather than archetypes. I’ve had the chance to peek inside dozens of organizations undergoing leadership transitions and a resounding, perpetual theme has been that after a period of elation, the new leader of color faces a level and type of pressure and scrutiny that their predecessors did not. And that extra scrutiny led many of them to leave or be pushed out.

This isn’t a defense of incompetence or bad leadership. It isn’t to presume that every piece of luggage the new leaders bring in the door should be given quarter. It is, however, important for us to reflect, in this moment especially, on the expectations that we have of our leaders of color. I wrote about this last year for NPQ and call it the Black Leader’s Burden. By which I mean: the additional weight leaders of color are saddled with beyond the job is both a function of the gauntlet we require them to run to get into the c-suite and the unrealistic expectations that we place on them to fix our brokenness.

What were we holding in our heads and hearts when the new leader of color was hired? Did we expect them to be our friend? Our mentor? Our healer? Our savior? What I have found is that the unspoken expectation has been for the new leader of color to take care of the organization and the people in ways their white counterparts and predecessors were not. And as we ask ourselves why America chose a mean, entitled, bigoted, dangerous, morally abhorrent man with a criminal record over a woman of color who dedicated her life to service, we have to ask not only how we could let this happen but how the traces of white supremacy and patriarchy live within our organizations as well.

This past year I had the unique opportunity to partner with an organization to write its racial equity and inclusion story. I’d worked with the organization for several years, which was long enough to convince me that racial equity wasn’t a service they provided but a way of being in the world. I wanted to understand how they had gotten there. Initially, they hesitated. They invariably reminded me that they were still a work in progress and had a long way to go. To which I steadfastly replied, who isn’t. Moreover, that is the point. Those of us who are doing work that can broadly be classified under the DEI banner have not done ourselves any favors by not openly, persistently and aggressively telling our stories. Because we have this notion that we are going to arrive at this future destination at which point we will be ready to talk about how we made it coupled with deep fear around how we will be perceived, everyone who has sat through an unconscious bias training and felt the slightest bit annoyed that it didn’t solve all of the organization’s problems overnight has had free reign to thoroughly shape the public’s understanding of the work.

Eventually, I convinced them to trust me. The first request that I made to the team once we agreed to the project was to see everything the firm had done to date. Within a few days, we received a link to a suite of folders containing rubrics, survey results, and memos all going back several years. We were amazed by what we encountered. The firm had been capturing its journey and tracking its progress all along. More directly: what I discovered in those folders was that the organization wasn’t just telling others what to do and how to do; it had turned the lens inward to do its own rigorous racial equity work. The more we learned about the firm’s internal, relational work through our interviews, the more convinced we became that this was what readers could relate to and could learn from.

All told, we spoke with two dozen current and former staff, board members, affiliates and foundation partners. These folks were generous and courageous in their sharing. They told hard stories of hurt feelings and unmet expectations, but they also told us about the organization’s persistence and its progress. Our task was to blend their voices along with the documents that we reviewed into a series of digestible narratives that deliver insight and action steps. Broken into eight distinct but overlapping chapters, the result is a series of vignettes that revolve around one organization’s efforts to advance, amend, embrace and embed our shared racialized inheritance across a period of time that began roughly a decade ago.

So what did we discover? A lot. But while the whole list is rich and will be sure in 2025, I’ve chosen a handful that I believe are essential to practice in the coming year. As you read them, I only ask that you think about these questions for yourself, on your own. That’s all:

Where do you see your own opportunities to lead or grow?

Where do you need more guidance and clarity from leadership?

What do you deeply desire for your organization?

What is the most essential work that you believe your organization needs to do at this moment to continue advancing its DEI?

I want to end this with a pair of reflections and an offering that has helped me remain hopeful.

The first: I recently led a series of REI workshops for an organization that works on one of our most urgent issues. It was a good work and people gave what they could. But what I found, by and large, was that people were too burned out to engage in the work being asked of them. It disappointed me because, as I pointed out to them and believe it to be true, they can’t do their best work if they can’t talk openly and honestly with one another. They can’t change the systems if they can’t be real with one another. Their best ideas won’t flourish. Fresh voices from unsuspecting corners of the organization won’t be heard–heck they won’t speak up. Yet even after I said this, folks remained silent, off camera–eyes averting each other. I got it. I understood.

The second: A few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a long profile on the University of Michigan’s decade long DEI efforts. This section really stood out to me:

“D.E.I. 1.0, the school promised, would be rigorous and evidence-based. Each of the university’s dozens of “units,” from the medical school down to the university archives, was instructed to devise its own plan; many set up miniature D.E.I. offices of their own. The initial planning ultimately yielded nearly 2,000 “action items” across campus — a tribute to Michigan’s belief in the power of bureaucratic process to promote change. “It’s important to focus on our standard operating procedures and worry less about attitudes,” said Sellers, who was appointed Michigan’s first chief diversity officer. “Attitudes will follow.”

The article’s conclusion was that the university has spent millions yet the progress it has made to date has been, at best, modest and more likely non-existent. More recently, and in part due to the article, the university has started rolling back its DEI practices.

In planning to spend time with you, I thought about both of these encounters. To me, there is a link between them. My hypothesis is that, for now, and especially as it relates to our external work, we have reached an impasse. It may be the case that because of the social and political climate we are entering we won’t be able to influence the external environment for the foreseeable future.

Our inability to directly influence and shape the external environment in alignment with our values could cause us to turn further inward, to close ourselves off from one another. It could fuel further angst and distrust and erode our coalitions from within.

Or it could be the invitation that we need to reconnect with one another. In hindsight, the period that will always be known as the racial reckoning was imperfect in many ways, but the trauma that we shared bonded us and through those bonds we had conversations. I’m not suggesting that we need to return to that time, but we are entering a dark period and we will have decisions to make about how we are going to extend ourselves, especially in these remote environments, to bridge our communities.

The silver lining here is that the renaissance of equity work that I believe we have been living through over the past handful of years was, in fact, the outgrowth of decades of darkness. My belief is that we were ready with action items because many of us had spent extended time in the shadows refining our ideas within our quiet communities, waiting for the right opportunity to bring them forward into the world. We didn’t just find out about discriminatory hiring practices in 2020. That research was two decades old when it finally started to result in reforms. The same can be said of Brown v Board. We know that 1954 was the year of that landmark decision but Thurgood Marshall spent the better part of 20 years building the case law and precedent so that when the moment finally arrived, the NAACP was ready. And let’s keep in mind, America didn’t pass its first federal anti-lynching legislation until 2022.

All of which is to say, we have work to do. Even if that work won’t result in changes tomorrow or the next day, that work is important because it lays groundwork for the next wave of opportunity, which, history and the laws of physics dictate, will come. So we can be down on each other or we can use this time to strategically plan the next phase of the struggle. We can, as Sherrilyn Ifilll wrote on her Substack the day after the election, plant the many seeds that we will need to grow in the years and decades ahead. If we do, though, we are going to have to recommit ourselves to being in a relationship with one another.

So today I want to end with the work of the poet, Audre Lorde. In 1982, Lorde delivered a talk at Harvard on the occasion of a celebration of Malcolm X's life and legacy in which she reflected on the 1960s. The essay is 42 years old but she speaks to the collateral damage of the reckoning we find ourselves in today

“In the 1960s, the awakened anger of the Black community was often expressed, not vertically against the corruption of power and true sources of control over our lives, but horizontally toward those closest to us who mirrored our own impotence. We were poised for attack, not always in the most effective places. When we disagreed with one another about the solution to a particular problem, we were often far more vicious to each other than to the originators of our common problem.”

That disagreement eroded the energy that folks needed to fight. It depleted folks. It burned them out. So, for Lorde back then and for me now, I offer the following reminder, coda, call to solidarity–whatever it needs to be to bring us into community.

“You do not have to be me in order for us to fight alongside each other. I do not have to be you to recognize that our wars are the same. What we must do is commit ourselves to some future that can include each other and to work toward that future with the particular strengths of our individual identities. And in order to do this, we must allow each other our differences at the same time as we recognize our sameness.”