A Complicated Honor

On recognition in a time of institutional crisis

In 2025, we watched institutions bend, break, and quietly accommodate the return of a man who had already incited an insurrection after losing an election that followed a disastrous term in office. Faced with that reality, many of us spent the year trying to understand where the breakdown happened and why. Some of us placed the blame in an antiquated electoral system. Others pointed to the right’s capture of the Supreme Court, gerrymandering, big money, morally bankrupt technology platforms, an enfeebled Democratic party, widening inequality, a precarious labor market, or the steady erosion of public trust. Each of these explanations contains truth. But taken on their own, none felt sufficient to me.

Part of that insufficiency has to do with history. Institutions have repeatedly promised my people order, protection, and opportunity, then withdrawn those commitments the moment they decide the balance has tipped too far toward justice. Terms like “tradition” have often been used as a gatekeeping mechanism — a way to keep people like me out while insisting that exclusion was simply the natural order of things. So I’ve always been wary of institutions that invoke history without interrogating it. I don’t challenge institutions because I want to burn them down. I challenge them because I want to know whether beyond the prestige, longevity and symbolism they hold, they still matter now.

That posture has shaped my work as a writer, as a strategist, as a facilitator, and, more recently, as a coach. Whether I’m writing about an institution or working inside one, whether it’s a startup or a storied organization, I’m interested less in what something or someone claims to value than in how those values hold when conditions change. I watch what flexes, what fractures, and what is quietly reinforced. What gets delayed or downgraded, what gets elevated and centered. Who is invited in, and who is bypassed. In moments of pressure, institutions, including the people who run them, show us not who they aspire to be, but who they are prepared to become if need be.

What 2025 did to me was strip away any remaining distance. The history I have studied and what I was watching fused, and I could no longer pretend these were separate failures. They were fractures of the same structure, revealed all at once.

If our institutions could not repel Trump—or could be twisted to produce him again—then the story we tell ourselves about institutional safeguards is largely a fiction. From that recognition came a reckoning my ancestors knew well and I could no longer avoid: legitimacy cannot be assumed. If institutions failed to protect us from the forces now reshaping public life, then legitimacy must be rebuilt—and that obligation belongs both to institutions themselves and to those of us deciding how, and whether, to remain in relationship with them.

A number of the essays I wrote in late 2025 attempted to respond to a call I felt to renegotiate our relationship with institutions—particularly the way they invoke tradition to justify authority, continuity, and legitimacy without accountability. But as the year closed, I found myself wondering whether I was missing something essential. As much as that realization clarified things, it still felt incomplete. There seemed to be something else happening to institutions beyond simple collapse.

Under Trump, the institutions in which we have collectively invested such faith have become playthings—used and abused at his whim. The metaphor that comes to mind is the Army of the Dead in Game of Thrones. In the show, thousands of reanimated corpses lurch lifelessly across the landscape, haunting the living. In our real lives, institutions continue to operate and function even as they serve as vessels for one man’s corruption.

On one hand, his administration has spearheaded a coordinated effort to discredit and dismantle the liberal institutional project altogether—schools, universities, media, courts, and the broader frameworks that have underwritten public life for decades: climate and energy policy, public health, international cooperation, multilateralism—the very idea that shared problems require shared responsibility. Expertise is reframed as elitism. Collective action as weakness. Governance itself as suspect.

On the other hand, we are witnessing an aggressive reassertion of racial and religious hierarchy, along with demands for ideological purity, coordinated by the state and enforced through its institutions.

To put it plainly, we find ourselves trapped inside an institutional paradox. The very instruments of democracy are being hollowed out and weaponized en masse, at the same time. On top of that, we are being asked by these same institutions—universities, media, and others—to operate as if the world isn’t broken, even as we can see the wreckage before our eyes. Universities keep enrolling students while the future of work and education is up for grabs. The New York Times and The Washington Post keep sending me New Year’s sign-up deals, as though the spectacle of democracy’s death by a million articles were just the latest sales pitch.

And while all of this is happening, we are left to our own devices, to make sense of the predicament we are in and how it should inform the society we will build after this phase—as all phases—ends.

Confronted with this challenge, some of us have retreated into the past. Over the past week or two it seems as though every major publication has weighed in on the internet’s wistful yearning for 2016. It’s as if many of us are saying, If I could just get back there, to that moment, knowing all we know now, everything could be corrected. I can appreciate that impulse. That was the year I met my wife and my entire life changed for the better.

But nostalgia is not a substantive or sustainable response to crisis. All we need to do is look to the MAGA movement to see how corruptible the past can be. Nor is it convincing when the richest man of all time proclaims that AI will enable the age of abundance, eliminating the need for retirement savings.

We can not afford to sleepwalk or wishfully think our way forward. With so much being turned inside out and upside down, we each are being challenged to develop our own strategies for staying sane and operating with clarity. Just as survivalists prepare for doomsday scenarios, moments like this demand their own form of preparation—for living inside a world that still looks intact while its foundations are being hollowed out.

What I kept returning to was how does one live with integrity inside institutions that no longer deserve unthinking trust, yet still shape the world we are moving into, and often in ways we cannot opt out of.

Then last week, that question stopped being abstract.

In the middle of an afternoon of Zoom calls and check in emails, my phone buzzed. It was a text from my mom. She’d just spoken with an old friend who wanted her to know there was a profile featuring me in the Sidwell Friends magazine. She sent screenshots. It was the second week of the new year, and the message landed like I was catching an accidental glimpse of myself in a mirror. I’d spoken with the writer twice back in October—once in an airport, once while my kids played in the next room—and then more or less forgotten about it. Some part of me feels so uninteresting that I assumed once an editor saw the draft, they’d decide the whole thing was a mistake and quietly make it disappear.

When the physical magazine arrived in the mail a few days later, I sat with it quietly without reading it myself or telling anyone about it. I wasn’t sure what to do with it. Whether to share it. Whether sharing it would feel indulgent or distracting at a moment when the demands on our attention feel relentless. I overthink these things. I can admit that.

Then a friend came over on Saturday night. He was the first person I showed it to.

He read it, looked up, and said—without hesitation—you have to share this.

That moment made the question I had been working through alive.

The issue wasn’t whether the piece flattered me or accurately captured me. The writer listened. He made an honest effort to render a life that, from the inside, rarely feels coherent. I’ve been on the opposite end of a profile so I know that reading your words back to yourself—arranged by someone else’s attention—is disorienting no matter what. Some of it feels accurate. Some of it feels frozen. But if there is care in the attempt, and there was, then that’s all I can really ask.

This question I found myself sitting with was what the act of sharing it—or choosing not to—signals about my own relationship to institutions in a moment of institutional crisis. Institutions don’t only confer meaning by claiming people. They borrow legitimacy from those they choose to elevate. I don’t pretend not to understand the risk embedded in that reciprocity. Institutions can spotlight individuals in order to insulate themselves from critique by proximity. That possibility sat heavy with me. I asked myself plainly whether my presence in this story at this time functioned less as reflection than as shield.

Sidwell Friends is one of those institutions people know. Outside of Washington, D.C., the name carries weight. Inside the city, it’s coveted. Aspirational. The attendance of the Obama girls during their parents’ tenure in office only added to its allure. The fact that it has now become a boys and girls basketball powerhouse nationally is one of those facts that sounds made up until you see the banner hanging in the gym.

I’m also aware of the critiques that accompany that reputation—critiques I’ve shared myself at different points.

When I published a book that was in many ways called the school out, they invited me to give a community talk. During the pandemic and the racial reckoning that followed, the school reached out and asked me for help. I worked with staff, the board, and school leadership. Later came a phone call informing me that I’d been chosen to receive a Distinguished Alumni Award. I didn’t apply for the award and still don’t fully understand what the evaluative criteria was. Then, this past fall, they reached out again to ask whether I’d be willing to talk about how I am making sense of the moment, the backlash, the strain on the very values they claim to teach.

Taken together, the pattern is hard to ignore. In moments of uncertainty, when they were trying to understand who they needed to be, Sidwell reached out with an ask or an invitation. And considering that I do not send my children to the school nor do I write a five figure check annually, that has to mean something.

Adding it all up, the ledger tilted toward sharing, so I am—but with a caveat, and on my own terms, as part of this essay.

What I don’t want is for the story to circulate untethered from the questions it raised for me, or stripped of the context that gives it meaning. Sharing it through my own reckoning, and with people I sense by the mere fact that you keep coming back will understand my inner struggle, rather than as an artifact passed along for consumption feels like the only honest path forward.

There is a version of this essay that ends with who might read it—a current student, a parent weighing whether to trust their child to the school, not to mention part with a boatload of money, a recent alum standing at their own crossroads. That reflection matters. Institutions shape lives long before they issue credentials, and the stories they tell about success do real work in the world.

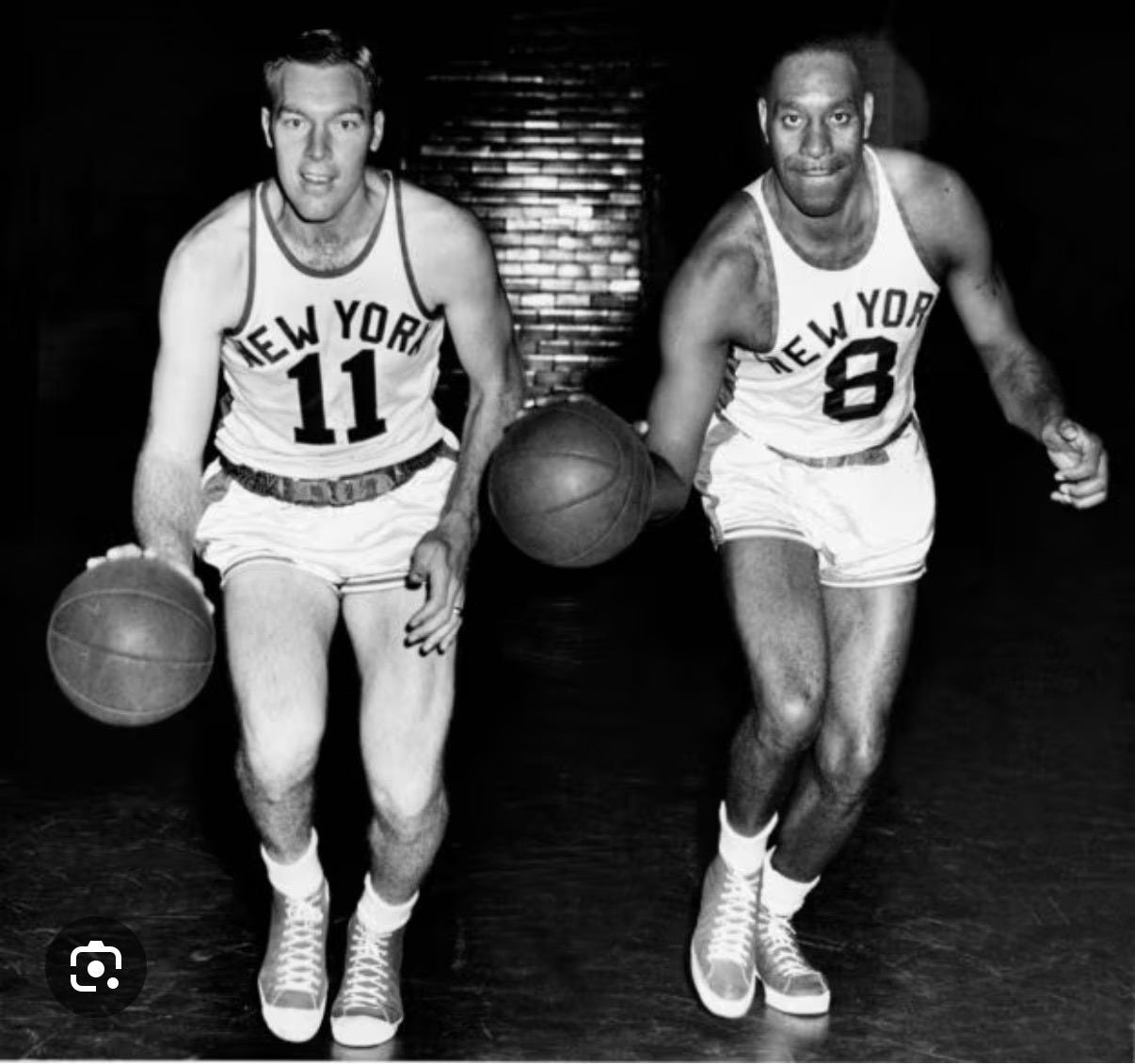

Fact is, as a teenager, I imagined being remembered, if at all, for basketball. I dreamt of having my name etched in the school’s record books. Now when I return for games, I slide quietly into the rafters to watch a team I’m not sure I could have made, accepting that to these players I am, literally, these guys:

Back then, it never crossed my mind that decades later I’d be reflected back as a writer, a strategist, someone working in the space between institutions and change—and that the life I built there would feel, in its own way, like a deeper kind of victory.

But that isn’t where I want to leave this.

What I keep returning to is my hesitation—the pause before sharing this piece at all—and what that pause revealed. It wasn’t only about discomfort with attention, though that was part of it. In a moment when the world feels saturated with urgency, when there is so much more worthy of people’s time than any single profile or reflection, asking for attention is a big deal to me.

The deeper hesitation was about consistency. About what it means to hold a sustained skepticism toward institutions and then call attention to an institution when that attention happens to revolve around me. That tension matters. Being clear matters. Having a stance means being willing to test it not only when institutions fail, but when they recognize.

This is one of those moments where values stop being rhetorical and start becoming practical. Where the work shifts from critique at a distance to reckoning up close. From throwing rocks at institutions to standing inside the frame and asking what responsibility looks like there.

I don’t think this challenge belongs only to me. I think many of us are being pressed, in different ways, to confront some part of our belief system right now—to ask what we are willing to carry forward into whatever comes next. Institutions will not disappear. They will be reshaped either by force or by intention.

This season of bad news and unvarnished authoritarianism is not something to be merely endured or cataloged. It is also a pressure test of our thinking, our commitments, our habits of action. And it invites something harder than outrage: a willingness to examine which assumptions are being stripped away, which stories about power and legitimacy no longer hold, and how we might refine—not retreat from—our sense of responsibility when the guardrails fail.

There will be a world after this. We will have to put it together. What matters now is how we meet it and what we demand of ourselves as we decide which institutions deserve to shape the future, and who we are willing to become in the process.

The tension between institutional critique and institutional recognition is real. What stands out is the refusal to let recognition function as absolution, the institutions borrow legitimacy from who they spotlight makes the transaction visible in ways most profiles obscure.Lived this in consulting where clients would promote diverse voices while ignoring systemic feedback. The choice to share it on your terms rather than let it circulate untethered is the move.